A WOMAN AHEAD OF HER TIME

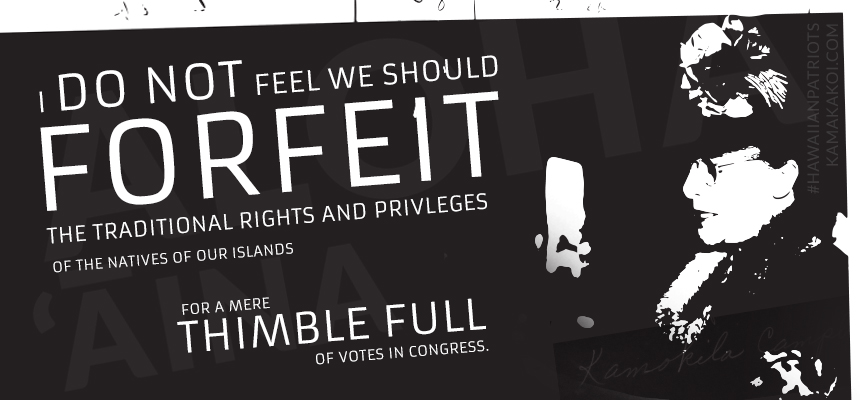

During the territorial period (1900-1959), Senator Alice Kamokilaikawai Campbell was a notable force in Hawai‘i and the strongest Hawaiian opponent of statehood. In these difficult territorial years, Kamokila's actions continued to breathe life in the spirit of aloha ‘āina. Her statements against statehood would foretell Kanaka voices today seeking greater rights and autonomy for Kanaka Maoli who -- through historical injustices -- have been forced to live in the construct of the State of Hawai‘i and the United States.

Kamokila, as she was commonly known, lived from 1884 to 1971. Her mother was Abigail Kuaihelani Maipinepine Campbell, head of the Hui Aloha ʻĀina o nā Wāhine and a lead organizer in gathering the 1897 Kū‘ē petitions against U.S. annexation. Kamokila’s father was businessman James Campbell. Thus, she and her sisters became heirs to the Campbell Estate and were among the elites of both Hawaiian and haole society in the islands. Early in her life, Kamokila married local businessman Walter MacFarlane and had five children, including well-known local waterman Walter MacFarlane Jr. and composer Muriel Macfarlane Flanders.

Kamokila commanded much mana as a striking and charismatic Kanaka who understood how to wield her strengths and her flair for the dramatic. After her divorce from MacFarlane, Kamokila embarked on a career in electoral politics, challenging assumptions that Hawaiians (and particularly Hawaiian women) were incapable of self-government. She served as a territorial senator representing Maui County from 1942 to 1946, also becoming Democratic national committeewoman.

During this period, she responded to requests from her constituents to look into the Native American reservation system. She also explored the possibility of placing the Hawaiian Home Lands under the Bureau of Indian Affairs. However, her meetings in Washington, D.C. convinced her that this was not a good alternative. In fact, in 1944, she requested U.S. Congressman Sterling Cole of New York to sponsor a bill that would transfer Hawai‘i from the Department of the Interior to the Naval Department, as a way to limit the flow of immigration to Hawaiʻi (as it had in Guam) and prohibit non-natives from owning land (as it did in American Sāmoa).

In January of 1946, a U.S. Congressional Committee (Committee) held hearings over a number of days. Kamokila arranged to provide her testimony at ‘Iolani Palace on January 17, the 53rd anniversary of the illegal U.S.-aided overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

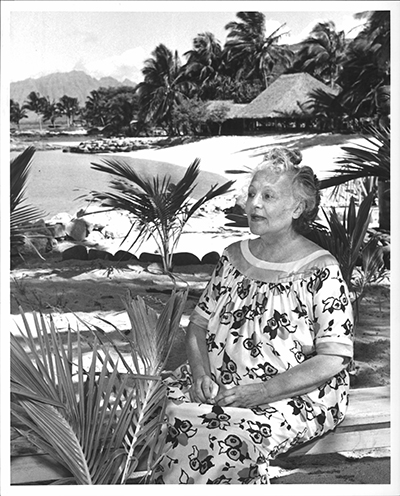

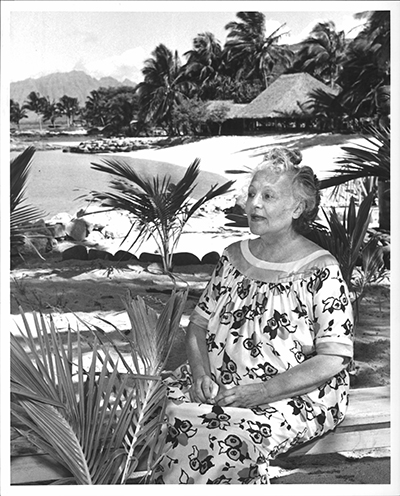

Kamokila, an heir to the Campbell Estate, was among the elite

of both Hawaiian and haole society in the islands. She commanded

much mana as a striking, intelligent, and charismatic Kanaka.

-- Hawai‘i State Archival Photo

The Committee agreed to devote a full day to her testimony. Kamokila Campbell appeared in a black holokū with red and yellow lei. On this and many other occasions, Kamokila connected the injustice of the overthrow to the inadequacy of reconciliation afforded by statehood. She spoke for over two hours advocating for Hawaiian self-governance and criticizing the greed of the Big Five corporations (Alexander and Baldwin,1 Castle and Cook, Amfac, C. Brewer, and Theo H. Davies), which would greatly benefit from statehood. She spoke of the economic control they had over the islands and its people and how such control negatively impacted everyday people, including Native Hawaiians. She stressed that the Big Five’s advocacy for statehood made it incredibly difficult for most people -- many of whom worked for the Big Five -- to speak out against statehood for fear of losing their jobs. Her speech stood as the most noted public position against statehood through the next decades.

Unlike most people at the time who had forgotten or purposefully pushed aside the decades-old problem of the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Kamokila insisted on keeping the overthrow in the conversation. She connected the control imposed by the U.S. at that time to the greater problems Native Hawaiians would face under the increased control that statehood would bring to the already powerful Big Five.

Kamokila’s bold moves to further the cause of Native Hawaiians and to publicly criticize the Big Five ultimately ended her political career.

Undaunted, she continued to call attention to the injustices of the overthrow and the improper coercion of Hawai‘i’s people in the push for statehood. Strategically, on January 17, 1948, Kamokila filed a lawsuit, Campbell v. Stainback, et al., regarding the illegalities of the government’s use of public monies to campaign for statehood. This successful lawsuit went to the Hawai‘i Supreme Court, where they ruled in favor of Kamokila Campbell, finding that such use of public funds was to the detriment of taxpayers who desired other forms of government.

Kamokila Campbell, in many ways, could be hailed as one of our last true ali‘i -- an elite woman born into affluence and high social standing who used her position to give voice and strength to her people. She spoke out at a time when all others were silenced by the political and economic might of the Big Five. In doing so, she is a vital link in the unbroken chain of Hawaiian patriots who have not and will not forget the travesty and injustice of the overthrow and the long-overdue reconciliation required.

*This biographical statement draws heavily on the research of Dr. Dean Saranillio. See resources section.

1. Alexander and Baldwin’s continued use and control of public trust water on Maui, is the topic of another Kamakakoʻi presentation, Ola I Ka Wai.↩

Kamokila Campbell, Keeper of Moʻolelo

Personal reflections of Kamokila Campbell shared in an interview with OHA Trustee Oswald Stender,

Lā Kū‘ōko‘a, July 31, 2014

“I first ʻmet’ Kamokila Campbell when I was a student at the University of Hawaiʻi. We would gather at Hemenway Hall where she would share moʻolelo. She was a wonderful storyteller!” recalls Office of Hawaiian Affairs trustee, Oswald Stender. “That was back in the 1950s. This was many years before I came to know her well in my capacity as a Campbell Estate Property Manager and CEO."

"It was a different time then, before the 1970s Hawaiian Renaissance. It was an era when it was not popular to be Hawaiian and Hawaiians were often looked down upon. Hawaiian traditions were reduced to being called 'superstitious' or 'fanciful.'"

But Kamokila knew better and made sharing moʻolelo a passion. “She wanted to ensure that moʻolelo would not be forgotten. She took time to come to the University to share these traditions with us young students. And it worked. I may not remember the details of every moʻolelo, but the importance of those moʻolelo has stayed with me,” says Stender.

Kamokila even brought Hawaiian moʻolelo into the popular mainstream. To record moʻolelo for all to enjoy, she sought the musical genius of Jack de Mello (father of musical producer Jon de Mello). He would write an original music score and have it performed to offer a moving setting for her storytelling. “It was quite a production. Her voice, Jack’s orchestra ... all very beautiful.”

Kamokila Campbell and Jack

de Mello consult with one

another while recording

Kamokila: Legends of

Hawaiʻi

--

Image provided courtesy

of Jon de Mello.

At the same time, Kamokila was deeply involved in Hawaiʻi politics. And in that context, the crucial moʻolelo that she would often bring to the fore was the illegal overthrow of 1893. “Kamokila would talk about the overthrow at every opportunity she had. It was important to her that people understood that there was a terrible wrong done that needed to be redressed,” recalls Stender. For Kamokila, moʻolelo -- whether of times long past or just decades fresh -- had import to everyone in the present.

This passion for moʻolelo was also part of Kamokila’s everyday life. Stender remembers, “When I would visit her at her home, she would tell me all about the area. She knew it intimately. This was a very special place for her. I remember making the mistake in my early days of thinking I could bring my net to fish there since the fish were so plentiful. Little did I know that she placed a kapu on those fish, and no one -- and I mean no one -- could touch them! She was a very serious kahu of that area. She loved that place.”

A woman deeply rooted to traditions, Kamokila understood how preserving the moʻolelo of an area and its natural resources came hand-in-hand with maintaining its mana, people’s respect for the area, and ultimately its abundance.

That abundance she understood was not for her own benefit but was to be shared. “Kamokila would open her residence for special occasions, and invite all of her friends to enjoy the idyllic setting,” said Stender. “It was like an oasis in the desert.”

Kamokila exemplified aloha ‘āina through

her warmth, generosity, and undying

passion for the precious traditions of

Hawai‘i and its people.

Above: Kamokila

at home, in a place that would later

become known as Lanikūhonuna.

-- Star Advertiser Archival Photo, 1964

“I remember a conversation I once had with Kamokila. She told me ʻLanikūhonua’ means ʻwhere the heavens meet Earth.’ So later, when I was the CEO at Campbell Estate and we were preparing the property for community cultural uses, I recalled my conversation with Kamokila and -- in a matter of speaking -- had Kamokila name the area: Lanikūhonua. I think she would have liked that,” said Stender.

Her willingness to share her home with others was the same approach she took with her financial resources. “Each month Kamokila had checks prepared for certain families that she knew needed her help. She was quite generous,” recalls Stender.

“Though her position in society and her own mana could make her an imposing figure, my strongest memory of Kamokila is of her warmth, generosity, and undying passion for the precious traditions of Hawaiʻi and our people.”

Online Resources

- Imi Pono: Statehood Hawai‘i

An archive of video presentations on the controversy of 1959 Statehood, created in 2009.

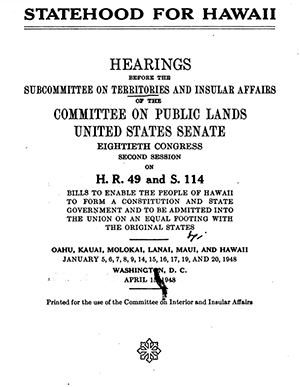

- 1948 Hearings on Statehood for Hawaii.

Hearings before the Subcommittee on Territories and Insular Affairs of the Committee on Public Lands, United States Senate, Eightieth Congress, second session, on H. R. 49 and S. 114, bills to enable the people of Hawaii to form a constitution and state government and to be admitted into the Union on an equal footing with the original States. United States. Washington, U. S. Govt. Print. Off., 1948.

- 1897 Kū‘ē petitions against U.S. annexation

Kamokila's mother, Abigail Campbell, was a lead organizer in gathering signatures for the Kū‘ē petitions. What were the petitions about? Watch a short video presentation produced by Na Maka o ka ‘Āina.

Printed Resources

- “Text of Kamokila’s Speech” Honolulu Advertiser. January 18, 1946. P. 8-9.

- Mellen, Kathleen Dickenson. “The Incomparable Kamokila: Kathleen Mellen Recalls Mrs. Campbell’s Greatest Coup d’etat: She Blitzed the Election on Maui,” July, 1962.

- Saranillio, Dean Itsuji. “Colliding Histories: Hawai‘i Statehood at the Intersection of Asians Ineligible to Citizenship’ and Hawaiians ‘Unfit for Self-Government.’” Journal of Asian American Studies 13, no. 3 (2010): 283–309.

- Saranillio, Dean Itsuji. “Seeing Conquest: Colliding Histories and the Cultural Politics of Hawai’i Statehood.” PhD Dissertation in American Culture, University of Michigan, 2009.

- Whitehead, John S. “The Anti-Statehood Movement and the Legacy of Alice Kamokila Campbell.” Hawaiian Journal of History 27 (1993): 43–63.

Mele

- “The Royal Rain,” composed by Muriel Macfarlane Flanders (1909-2003), daughter of Kamokila Campbell, about the 1917 funeral of Queen Liliʻuokalani

- “Kamokila: Legends of Hawaii,” Mountain Apple Company, digitally remastered by Dean Hoofnagle. Originally recorded at Capitol Studios, Hollywood, California in September 1957; United Studos Hollywood, California in 1963. Spoken vocals by Kamokila Campbell, Conducted by Jack De Mello.

Kamokila, an heir to the Campbell Estate, was among the elite

Kamokila, an heir to the Campbell Estate, was among the elite

Kamokila Campbell presents her testimony

Kamokila Campbell presents her testimony

Kamokila Campbell and Jack

Kamokila Campbell and Jack