For generations the island of Kahoʻolawe, or Kohemālamalama o Kanaloa, has been a place of learning, training, regeneration, and subsistence for Kanaka Maoli. Like all of our islands, Kahoʻolawe is alive, and yet this life was threatened by the United States military for several decades, between the 1940s-1990s. Since the onset of the US military occupation of Ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina (the Hawaiian archipelago), numerous culturally significant and sacred lands have been subjected to extensive violence in the name of American national security. The U.S. Navy took control of Kahoʻolawe during World War II, and the island was used for live-fire and combat training, particularly to practice and simulate airfield attacks. U.S. allies participated in some of these training maneuvers as well. In 1965, the US Navy simulated a nuclear explosion on the island. The blast utilized 1 million pounds, over 450,000 kilograms, of TNT. In addition to leaving a massive visible scar on the land, the detonation caused valuable fresh groundwater to leak out from the island’s underground water table.

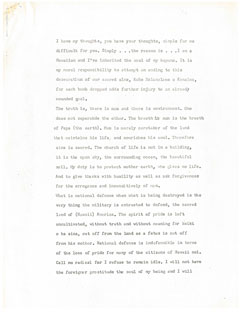

On a Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana (PKO)

On a Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana (PKO) access visit this ʻOhana member stands

at the edge of a massive crater created

by thousands of pounds of dynamite

that was exploded to simulate a

nuclear explosion.

-- Ed Greevy Photo Collection

Many of the people who became involved in the movement to stop the bombing of the island grew up watching, hearing, and feeling explosions and gunfire on Kahoʻolawe from across the channel. In January 1976 during the season of Makahiki honoring peace, a group of resistors landed on Kahoʻolawe. Although contingents from various islands gathered on Maui in an attempt to get across the channel, only one boat from Molokaʻi actually made it to the island. The nine people on board included Emmett Aluli, Kimo Aluli Mitchell, Warren Haynes, Ian Lind, Ellen Miles, Steve Morse, Gail Prejean, Walter Ritte, Karla Villaba and George Helm. A few weeks later, a second landing of four people--Walter Ritte, Loretta Ritte, Scarlet Ritte and Emmett Aluli--from Molokaʻi, was made.

In all there were nine known landings made without consulting U.S. Naval authorities, in direct defiance and opposition of the U.S. military’s authority over usage of the island. These landings not only required the courage, physical and spiritual preparation of those who landed; They required a broad network of supporters to help watch children, raise funds, make phone calls, locate and run the boats, and lobby elected officials. Additionally, over the course of several years beginning in 1976, spiritual and cultural leaders--such as Sam Lono, Emma DeFries, John Kaimikaua, Edith Kanakaʻole, Nālani Kanakaʻole and Pualani Kanakaʻole Kanahele--led ceremonies to re-open religious sites, and to begin healing the life of the land and people.

From 1976 - 1990 the Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana facilitated landings, work trips, and revitalization efforts to end the desecration. Beginning in 1980, the PKO entered into a Consent Decree with the U.S. Navy to allow for regular, but limited and monitored visits to the island. Although the bombing was halted in 1990 by a U.S. Presidential order and the island formally transferred to the State of Hawaiʻi in 1994, the work of healing the ʻāina continues to this day. The PKO continues to bring people to the island so that they might develop relationships with a place that has been essential in the revitalization of the lāhui Hawaiʻi.

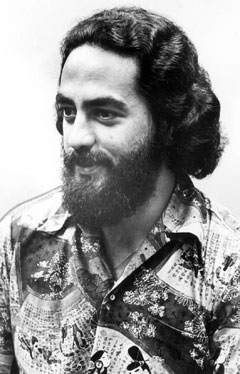

As the President of the Protect Kaho‘olawe ‘Ohana, George Helm led the group through its most active period of political protests. Through his leadership, and the dedication of many ʻOhana members, the hui emerged from being initially considered a “fringe group,” to becoming one of the most respected, effective, and supported organizations among Native Hawaiians and the general public.

VIDEO: "George Helm worked

VIDEO: "George Helm worked