REPATRIATION TRIP

In late August, Hui Mālama i Nā Kūpuna o Hawai‘i Nei (Hui Mālama) and the Office of Hawaiian Affairs sent a small team on assignment to bring home 144 kūpuna from the Natural History Museum (NHM) and one kupuna from the Welcome Trust, both located in London. An ‘Ōiwi TV crew was also part of the group and documented this historic event. The highlights below provide a glimpse into their experiences:

- Day 1: After 20 hours traveling, the group assembles in a private corner of their small hotel to review work plans and practice once more the pule, oli, and mele they will use in the necessary protocols and as ho‘okupu.

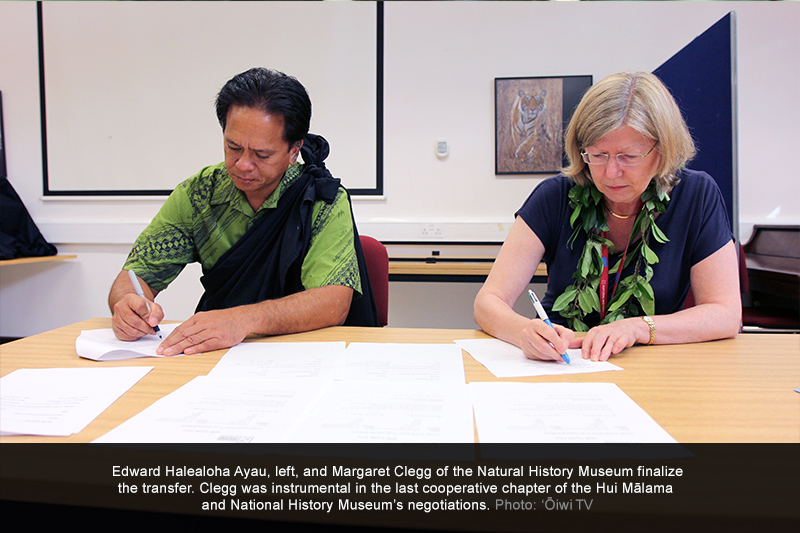

- Day 2: The team conducts protocols to prepare for the interaction that will occur between themselves and the kūpuna. Edward Halealoha Ayau (Executive Director of Hui Mālama) and Margaret Clegg (Head of the Human Remains Unit at NHM) sign the documents that transfer 144 kūpuna from NHM to Hui Mālama and the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. The team prepares the kūpuna for safe travels home.

- Day 3: The team goes to the Welcome Trust to repatriate one kūpuna from that institution. They return to NHM to continue their work to prepare the 144 kūpuna for a successful journey home.

- Day 4: The team conducts research on European-related repatriation matters.

- Day 5: 145 kūpuna and the team arrive safely at home.

- Upon return to Hawai‘i: Reburial plans are implemented, returning each of the 145 kūpuna to rest on their home islands of Molokai, O‘ahu and Hawai‘i.

Watch: Ka Ho‘ina: Going Home. ‘Ōiwi TV for Kamakakoʻi

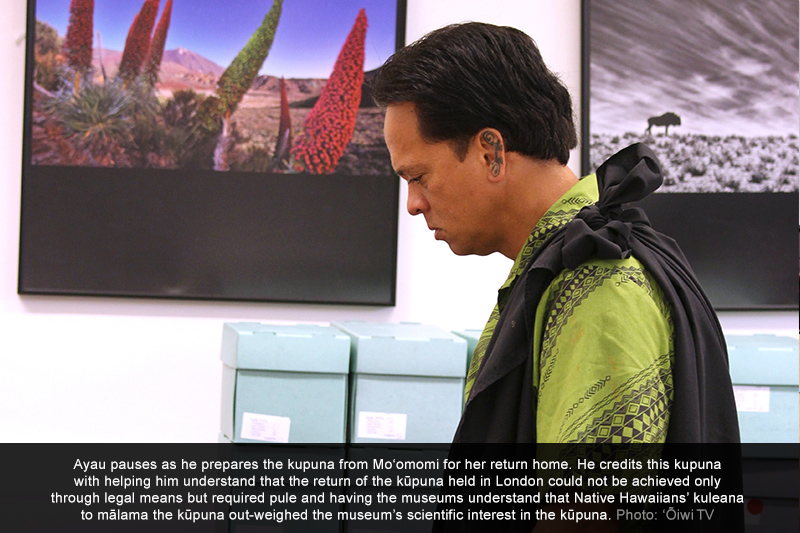

Long ago…cradled fondly in familiar arms, his aloha warmed her as he laid her to rest in her one hānau, her birth sands of Mo‘omomi, Molokai. The waves embracing Mo‘omomi’s shore and her gathered ‘ohana soothed her. In this new life, her boundless ‘uhane (spirit) would reside with her ‘aumākua. Her iwi (bones), rich with mana, would return to Papa, imbuing the ‘āina with her life’s mana. Her ʻohana would care for her burial sands. She would visit and mālama her moʻopuna (descendants), and they would heed her voice—a feeling in their na‘au (core), a vivid dream, an inner voice.

This was a year before Hawai‘i state burial laws and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act were enacted to protect unmarked burials and to require museums in the US to repatriate human skeletal remains to descendants. But the nearly 1,100 sets of iwi kūpuna (ancestral remains) disinterred from the dunes at Honokahua, Maui had already stirred this young Hawaiian attorney from Moloka‘i to locate stolen iwi and return them to rest.

Ayau recalled, “Bishop Museum explained that they gave the Mo‘omomi kūpuna to the Cranmore Ethnographic Museum in Kent, England, and that it had since closed. Its collections were split among several institutions.”

That was the beginning of a 23-year quest.

“When we started, the British wouldn’t respond to our letters,” said Ayau. At the time he was the Burial Sites Section Lead for the State Historic Preservation Division, and William Paty was the Chair of the Department of Land and Natural Resources.

“I thought if the State of Hawai‘i made the inquiries, we might get some answers. So I asked Mr. Paty if he would assist. I wrote a form letter, addressed them to 200 institutions, and Mr. Paty signed each one. Then the replies started coming in, but it wasn’t good news,” said Ayau.

The Keeper of Palaeontology at the British Natural History Museum (NHM, Museum) replied with a two-paragraph letter saying that they held “about 140 registered items from Hawaii…most of which are crania” and that they would release information of those items only “to bona fide scientific research workers.”

“Was the Mo‘omomi kūpuna there? I wasn’t sure. Unfortunately, that wasn’t the biggest problem,” said Ayau. “The number was far larger than we imagined, and without any information about these kūpuna, we were disadvantaged in arguing for their return. The problem was daunting. But we focused on what our kumu, Edward and Pualani Kanahele taught us. We would pule. We asked our ‘aumākua for help and we asked the kūpuna in the museums to aid in their own rescue.”

Edward Kanahele remained mindful of opportunities the kūpuna might present. A year later, Desiree Moana Cruz, Kanahele’s Hawai‘i Community College student requested to be excused from class for a trip to London.

“When we started, the British wouldn’t respond to our letters … I wrote a form letter, addressed them to 200 institutions … the replies started coming in, but it wasn’t good news.”

He agreed but asked her to meet with him and his wife Pualani about a possible assignment. They told her about the 140 kūpuna at the British Natural History Museum and the information needed.

Cruz and fellow model Priscilla Kekaulike Basque were guests of the Al-Sabah Family of Kuwait in London. At their first opportunity, they visited the Museum and found the proper department in a basement where records were kept.

The restraint of the records keeper melted when the pair turned on their local-girl charm. Unbeknownst to him, Cruz and Basque hand-copied the register they managed to have him reveal. There were 149 Hawaiian “specimens” in the collection from various locations, most of which were crania.

But a sign of the hard course ahead was in constant view before Moana and Priscilla. Just outside the basement window, they saw many bare feet at ground level. They were Australian Aborigines who, since the 1970s, were unable to gain the return of their iwi kūpuna. They were protesting the Museum.

But Ayau’s battle would take a different course. Armed with new data now, he drafted a six-page letter citing laws and court cases of ancient Rome, England, the US, and the Hawaiian Kingdom—all conveying that a human body, even a deceased one, cannot be owned by another. He established that the Museum’s possession of the remains was not equivalent to rightful ownership. He consulted with Kūnani Nihipali, Hui Mālama’s leader at the time, who approved the letter, signed it, and sent it off.

The Museum again denied the repatriation request, asserting that it was “precluded by the British Museum Act of 1963 from disposing of any items.”

In fact, the Act allowed trustees to determine if objects were “unfit to be retained.” They could dispose of such items, if doing so would not harm “the interests of students.” The Museum could weigh the value of the iwi kūpuna to science and consider whether Hawaiian perspectives or legal and ethical concerns might make the iwi “unfit” Museum possessions.

Ayau pondered what higher power would lend more weight to Hawaiian perspectives and called upon US Senator Daniel Inouye, whose office Ayau had worked for fresh out of law school.

He requested that Inouye seek support of the US State Department, which Hui Mālama already approached. In 1992, Inouye wrote to Secretary of State Warren Christopher urging the Secretary to offer his “assistance in the return of 149 ancestral Hawaiian remains.”

Hui Mālama wrote as well to British Prime Minister Tony Blair, the British Secretary of State, and the Cultural Division of the British Embassy in Washington, DC—eliciting courteous replies but little more.

Still, the response from the US State Department gave Ayau hope. They noted that change could come from “an act of Parliament.” It was a lofty approach that for the time was out of reach. But Ayau began brainstorming what he might convey, if ever he had the Parliament’s attention.

“I could feel them,” said Ipō Nihipali. “Their longing to be home made us uē (cry). We felt their ‘eha (pain). They knew why we had come. They were reaching out to us just as we were reaching out to them.”

Hui Mālama persisted in the intervening years, presenting the Museum with new analyses and potential solutions. But the Museum wouldn’t budge. And neither did Hui Mālama. “Uncle Ed taught us ‘you gotta believe first, then it will happen.’ We never stopped believing.”

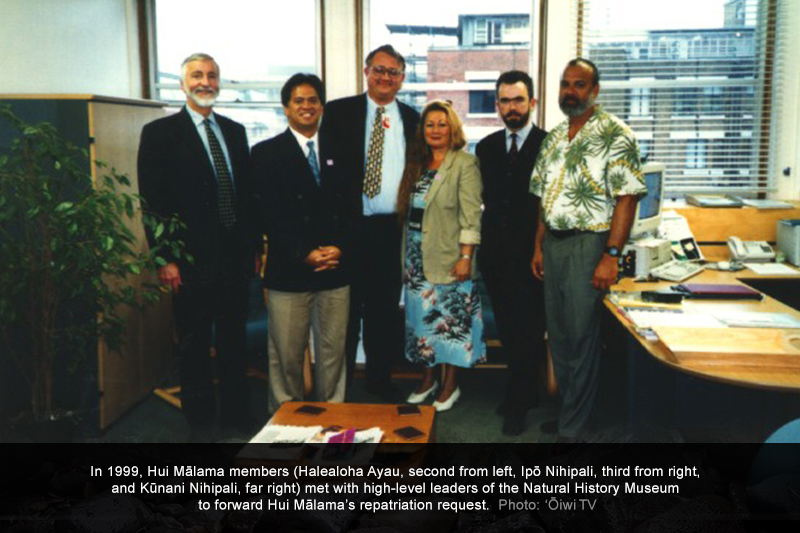

By 1999, Nihipali and Ayau felt they needed to develop a closer relationship with the kūpuna at the Museum and with the Museum’s leadership. The two travelled to London with the wahine balance of Hui Mālama, Nihipali’s wife Ipō.

By this point, Hui Mālama held stronger ground in the negotiation. It had emerged as a respected native organization, having then repatriated over 5000 individuals from 39 institutions across Hawai‘i, the US, Germany, Canada, and Australia.

“Before we met with the Museum leadership, we invoked our ‘aumākua, the kūpuna trapped in the Museum, and the kūpuna we repatriated. We asked that they kōkua; and they did,” recalled Ayau.

“It was a productive meeting. The Museum assured that they would cease further research and amend Museum policy so Hui Mālama, a cultural rather than scientific entity, could be in the presence of the iwi and obtain relevant information,” said Ayau.

As much as there was to be grateful for, disappointed lingered with the three, for they were disallowed from addressing the kūpuna on this trip. As they wandered the vast halls trying to sense where the kūpuna might be, they spotted one of the three Museum officials they had just met with. He was now gesturing discretely for them to follow him. He led them to a door, nodded at it and quickly left.

Just outside the locked door, the Nihipalis and Ayau tied on their black kīhei and began offering pule.

“I could feel them,” said Ipō Nihipali. “Their longing to be home made us uē (cry). We felt their ‘eha (pain). They knew why we had come. They were reaching out to us just as we were reaching out to them.”

“The Museum had the force of their laws, but we had the mana of our pule,” said Kūnani Nihipali. “We knew our pule activated them.”

JOINT REPATRIATION

Repatriation of the 145 kūpuna involved Hui Mālama and the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Hui Mālama engaged in the 23-year process to release the kūpuna (as shared in this article). OHA provided support letters and much of the funding for the London repatriation effort, the video documentation and the reburial of the 145 kūpuna.

Though the Hui Mālama group did not realize it at the time, the kūpuna were beyond the door, through a hall, down a stairwell, and in a basement sitting on rows and rows of shelves.

The sympathetic museum manager who led them to the doorway was part of a growing international movement among academics to develop a more balanced, meaningful relationship with their native subjects—a movement Hui Mālama helped to shape in their many interactions with museum officials.

Hui Mālama also agreed to numerous symposia presentations, including one at the University College of London, “Moving Forwards with Indigenous Peoples into the 21st Century,” where Ayau held the attention of a packed room.

“I wanted them to understand that Britain—compared to other maturing nations—was ignoring a fundamental human right to be laid to rest unmolested, and that their digging up our ancestors’ heads for curious scientific ‘needs’ was nothing short of barbaric. I tried to share our perspective and have them understand the ‘eha (hurt) they caused,” said Ayau.

On the heels of that presentation, Hui Mālama became one of only four native entities specially invited by the Parliament-established British Working Group for Human Remains to offer testimony to their group “on the potential return of human remains” from British museums.

Hui Mālama’s 24-page testimony became part of the record Parliament relied upon in passing in 2004 the Human Tissues Act, which enables institutions “to transfer human remains from their collection if it appears to them appropriate to do so for any reason.”

Upon the Act’s passage, Hui Mālama renewed its repatriation request. However, the Museum would address requests in historical order, and the Australian Aborigines were first. The Aborigines’ decision to sue the Museum took years to resolve—during which Hui Mālama’s claim waited.

In this period, the Museum continued archival research to ensure that iwi included in the potential repatriation were indeed Native Hawaiian, and forwarded their findings to Hui Mālama.

Ayau and his daughter Hattie created a spreadsheet of those records. As she read to him and as he typed the data into his computer, a 20-year-old question was answered.

Hattie said, “…Beasley No. 525 Cranium…Malakai…I think they mean Molokai…” And indeed they did. The Beasley Collection originated at the Cranmore Ethnographic Museum in Kent, England. It was the kūpuna that was transferred from the Bishop Museum in 1910, the kūpuna that started Ayau’s inquiry of the Natural History Museum in 1989.

“I sat there and the tears wouldn’t stop. I thought I’d never find her. And now I realize she was guiding me all along. I couldn’t wait to bring her home. I look out from my hale at Mo‘omomi every day. I’ve thought of her countless times,” recalled Ayau.

With energy renewed, Ayau checked and triple checked the records, and sent yet another repatriation request to the Museum. With the Aborigines’ lawsuit coming to closure, Hui Mālama’s request was finally brought before the Museum’s trustees.

“The day they met in November 2012 was nerve racking. They could have denied our request. It hinged on whether our plea to mālama our kūpuna outweighed the scientific “need” for them as “specimens.” And then I finally got the email with a scanned copy of their decision. I read the beginning of it and was really anxious because they were talking about the scientific value of the iwi. But three paragraphs in, I read the sweetest line: ‘The Trustees have decided to return the remains…to your organization.’”

“It still took nearly a year to negotiate with them all of the specifics of how and when the repatriation would occur. But it happened. On August 29, 2013, 145 kūpuna returned home.”

Each of them are back on their home islands, reburied and at rest today—in Puna and Kona on Hawai‘i, in Ko‘olaupoko and Kona on O‘ahu, and in the sands of Mo‘omomi on Molokai.

This article originally appeared in the October 2013 issue of Ka Wai Ola.