Kyle Nakanelua, a community farmer on Mau’i, looks over the millions of gallons of water that is still diverted from natural river sources despite court rulings that order their return to the streams of origin.Photo: Ruben Carrillo

“It’s crazy that we have to fight for something that has always been available”

Watch: Ola i ka Wai: Water is Life. 4Miles, LLC for Kamakakoʻi

For a glimpse of the latest hopeful sign in the ongoing legal battles over water rights in Hawai’i, look no further than the Nā Wai ‘Ehā streams in Central Maui. At these four wonderlands of ever-present rainbows, stunning verdant valleys and blazing sunsets, anxious anticipation from more than a decade of hearings and legal maneuvering has given way to a collective sigh of relief since the most recent legal victory for a broad-based alliance of farmers, environmentalists and others in the Native Hawaiian community.

The Aug. 15, 2012 Hawai’i Supreme Court ruling against the state Commission on Water Resource Management has provided some desperately needed clarity in the bruising power struggle over water rights in the central valley of Maui, where the last of the state’s once-powerful sugar plantations is clashing with farmers, who want to grow such traditional root crops as taro, and others interested in gathering native stream resources as well as exercising spiritual practices.

In its decision in the Nā Wai ‘Ehā case, the high-court upheld state law that requires the water commission to consider the effects of its decision on traditional and customary Native Hawaiian practices at streams. The high court also upheld state law that requires the commission to consider steps to protect these practices.

“The law has been clarified in all of the water cases that have been litigated, and yet, it’s something that unfortunately the water commission continues to ignore.”

— Kapua Sproat

Since the 1990s, communities in East Maui have been bringing attention to the raging controversy over the constitutional right in Hawai’i to protect traditional as well as customary Native Hawaiian practices at streams. It has also been a familiar showdown in Windward O’ahu, where the state’s high-court handed a group lined up behind taro farmers a significant legal victory more than a decade ago.

“It’s important for people to understand that these struggles are not about hand-outs or asking for something special.”

FOLLOW THE LAW

Fast-forward to today. Native Hawaiian farmers and others, in a coalition with environmentalists, are hoping that the latest high-court ruling in the Nā Wai ‘Ehā case will finally help correct an injustice and ease the emotional tension that battles over water rights have caused over the years in communities across the state.

“It’s important for people to understand that these struggles are not about hand-outs or asking for something special,” said Kapua Sproat, the attorney who is credited with initiating the Nā Wai ‘Ehā case in 2003 as a lawyer with Earthjustice.” The bottom line in all of these cases, and the cases to come, is about enforcing the law.

“The law has been clarified in all of the water cases that have been litigated,” Sproat said. “And yet, it’s something that unfortunately the water commission continues to ignore. And my hope is that going into the future, communities will not have to litigate these issues. If we appoint the right people to the water commission, the right decisions will be made and justice will be served. But we need to make sure that our water commissioners aren’t just taking up space — but actually understand what the laws are and have the moral ability to be able to do what’s right, as opposed to just doing what is politically right, or politically convenient.”

Watch: The rights of East Maui community farmers and downstream users are being ignored and laws are not being enforced. What’s going on? 4Miles LLC for Kamakako‘i

DAVID VS. GOLIATH

Perhaps the most significant water-rights slugfest to unfold in the courts came after O’ahu Sugar announced in 1993 that it was closing its operation. The announcement threw up for grabs about 30 million gallons of water per day that was being directed from the Waiahole Ditch System in Windward O’ahu to dryer central and Leeward plains, where O’ahu Sugar subsidized its operation.

On one side of the showdown in the Waiahole case were small family farmers and Native Hawaiians, led by citizen groups Hakipu’u ‘ohana, Ka Lahui Hawai’i, Kahalu’u Neighborhood Board, Makawai Stream Restoration Alliance and a coalition of supporters who sought to return diverted flows to the streams to restore native stream life, such as ‘o’opu, ‘ōpae and hīhīwai; protect traditional and customary Native Hawaiian practices; support the productivity of the Kāne’ohe Bay estuary; and preserve traditional small family farming, including taro cultivation.

On the other side were large-scale agricultural and development interests that urged the State to continue the flow of Windward water to leeward lands to subsidize golf course irrigation, short-term corporate agriculture, and housing development.

In a landmark high-court decision in 2000, the coalition group won the Waiahole case.

“The Waiahole case was a very significant legal victory because it was the first time ever in Hawai’i’s history that water was ordered restored to the streams and communities of origin,” Sproat said. “It was looked at by many in the community as a beacon of hope. It was a real David versus Goliath issue, where communities were able to persevere. It made it easier for other communities that wanted water restored to their streams. Nā Wai ‘Ehā and Waiahole cases are examples where Maoli communities have been able to seek not just a return of their resources for cultural practices, but an important part of reclaiming their sovereignty and being able to control their destiny into the future so that their culture can live.”

“There are challenges with the composition of the water commission, the majority of the commissioners are tied to major land owners, which raises red flags”

STILL LEFT OUT TO DRY

At the same time, coalitions of community groups have grown increasingly disillusioned with the water commission, which has been portrayed as having an aggressive indifference to traditional and customary rights of Native Hawaiians when making its decisions.

Just ask Alan Murakami, an attorney with the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation, who has been a pivotal figure in efforts to address the wrongs done to Native Hawaiian farmers in East Maui. In fact, he has generated positive headlines for his success in legally blocking decades-long leases to a subsidiary of Alexander & Baldwin that wanted to divert billions of gallons of East Maui stream water for sugar cane irrigation.

“There are challenges with the composition of the water commission, the central agency to regulate all water in Hawai’i,” Murakami said. “The majority of the commissioners are tied to major land owners, which raises red flags about appointments. And every water commissioner is supposed to have substantial water management experience.

“But that standard has not been applied, leading to a situation where you have a lot of people who have a background in the use and exploitation of water,” Murakami said. “We’ve had six reversals of water commission decisions, raising questions about whether the commission is being composed of people who are qualified under the statute.”

The state water commission declined comment through a spokesperson.

Even so, the hard truth about the Water Commission is it has allowed the Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Company to divert more water than it needed from East Maui streams at the expense of traditional and customary Hawaiian practices, Murakami said.

“The state constitution protects these practices,” Murakami said. “But the struggle since 2001 has been to try to get the commission on water resource management to put back enough water into streams to respect these practices. What we’re asking for is not unreasonable.”

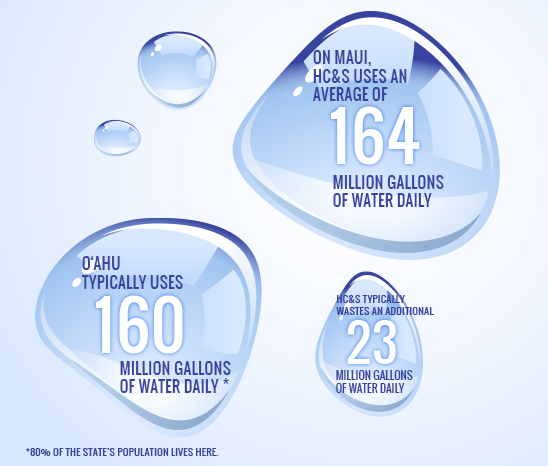

The Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Company uses an average of 164 million gallons a day, Murakami said.

By comparison, the entire island of Oahu — with 80 percent of the state’s population — typically consumes an average of 160 million gallons of water a day.

“So on Maui, one company is able to divert as much as all of Oahu,” Murakami said, adding that the company is wasting up to 23 million gallons a day through leaks in its irrigation system.

“The water we are asking to be restored is less than what these companies waste,” Murakami said. “You can’t tell me that our request is unreasonable. But politics and economics appear to trump the law.”

Edward Wendt is among the taro farmers in East Maui who has voiced frustration with the water commission, criticizing the seven-member panel for nurturing doubts about its commitment to properly enforce laws and questioning whether it could ever earn his trust.

“I’m hopeful that day will come soon,” Wendt said. “But right now it hurts hard. We don’t trust the water commission and we have justification for that. It has allowed private corporations to make money off a public trust and that is wrong. People are paying the price for our water resources being taken and sold off for profit.”

His sentiment is echoed by Kyle Nakanelua, an East Maui taro farmer, who characterized the perceived bias of the water commission as a serious problem for a state that, ironically, is focused on reducing its incredible dependence on imported food while hurting taro farmers who could help protect and strengthen local agriculture.

“It’s ludicrous that we have to fight for water,” Nakanelua said. “It’s crazy that we have to fight for something that has always been available. But instead of helping the people, the water commission would rather help friends that are building hotels and golf courses.”

THE OTHER SIDE

In defending his company’s position, Rick Volner, general manager of the Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Company, looks at the issue a couple of different ways. For starters, he said water is transported long distances to get it from stream to the 36,000 acres of sugarcane fields in Central Maui. It is these waters, from East and West Maui streams, that have enabled HC&S to exist and survive for the past 140 years, he said.

The ditch systems that transport the stream waters to HC&S’ fields are quite efficient, he said. The East Maui Irrigation (EMI) system consists of approximately 75 miles of ditch and tunnel; approximately 50 miles of the system in tunnel and 25 miles is ditch.

The system, he said, is efficient in transporting water, as the majority of it is lined (50 miles), thus reducing seepage, and evaporation losses are essentially eliminated in the 50 miles of enclosed tunnel due to lack of exposure to sunlight or wind.

As a result, the physical features of the system coupled with EMI’s management practices serve to minimize the inevitable losses of water from the system. A recent study performed by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) of the EMI system chronicles both the seepage losses and gains in the EMI system, Volner said.

“There inevitably are losses whenever water is transported for long distances, whether in a stream bed or in an open ditch,” Volner said. “These losses occur in the form of seepage, into the ground, and evaporation into the air. But neither is a ‘waste’ of water. In both cases, the water returns to the natural water cycle–stored as ground water in aquifers, or in the atmosphere returned ultimately as rainfall.”

He added that the bottom line is it would be cost prohibitive, if at all possible, to eliminate the remaining losses that do occur in the ditch systems feeding HC&S’ agricultural fields. “Even a completely closed system–pipes–would incur losses, transporting water for long distances,” he said.

Volner emphasized that there is a direct correlation between water applied to the sugarcane plant and the amount of sugar produced.

“We are fighting very hard to keep HC&S alive and to identify a sustainable future for HC&S that is right for the Maui community and our 800 employees.”

THE WAITING GAME

As for the August 2012 high-court ruling in Nā Wai ‘Ehā case, it was prompted by an appeal of a water commission decision in June 2010 to restore little or none of the stream flows diverted by two private companies — the Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Company., which is a subsidiary of Alexander & Baldwin Inc., and the Wailuku Water Co., which is the remnant of the now-defunct Wailuku Sugar plantation.

The appeal was filed by Maui community groups Hui o Nā Wai ‘Eha and Maui Tomorrow Foundation, which were represented by Earthjustice. The Office of Hawaiian Affairs also appealed the decision.

The court ruled that the commission failed to give proper consideration to the rights of Native Hawaiians and the public to the flowing streams. The court also ruled that the water commission needed to further explore credible alternatives to draining the streams, including perhaps eliminating inefficiencies, recycling wastewater or using non-potable wells.

In short, the court sent the case back to the water commission to redo its decision and improve its analysis of the amount of water that should be restored to the streams. While the community groups acknowledge that they are not looking to put the plantation out of business, they did stress a desire to help wring inefficiencies out of its operations.

Examples include forcing the plantation to fix leaks in dilapidated water systems and make sure they are not unnecessarily over-watering crops. “It’s now a waiting game,” said John Duey, president of the Hui o Nā Wai ‘Eha, which was formed in 2003 in direct response to concerns about diverted water from streams. “The law says what they are doing is not right; the law should be upheld. It’s time to put the water back.”

“The law says what they are doing is not right; the law should be upheld. It’s time to put the water back”

A SOURCE OF FRUSTRATION

At the center of the issue is the water commission and an aging irrigation ditch system built by sugar plantations more than 100 years ago that continue to drain the Waiehu, ‘Iao and Waikapu streams as well as the Waihe’e River, pitting sugar plantations against farmers who want to grow crops that have sustained communities for generations.

Since 2004, taro farmers and community groups have mobilized to restore water to the area, whose streams, romanticized in Hawaiian songs, was once identified as the largest continuous area of taro cultivation in Hawai’i.

Hōkūao Pellegrino, a Native Hawaiian farmer and cultural specialist whose ‘ohana owns kuleana land in Waikapu, has been outspoken about the adverse effects of diverted water from streams that flow near his family’s taro farm.

Pellegrino is quick to point out that instead of being able to effectively grow food and support his community, he’s had to scramble for minimal-to-zero access to water, adding that about 94 percent of the water from the stream near his family’s taro farm is diverted.

“The sugar industry has placed many challenges on the Hawaiian community, which has lost a lot of land to cultivation of sugar canes,” Pellegrino said. “Farmers have a right to access to water. And when you are the water commission, and you are making big decisions for the livelihood of a community, you need to understand the true impact that diversions have on farming.”

During a wide-ranging conversation about Native Hawaiian traditional and customary rights, Hōkūlani Holt, who has caught public attention on Maui for her contribution to teaching, promoting and supporting traditional Hawaiian culture, reflected upon a perspective that appears to get lost in the water-rights fights that end up in the hands of the court.

“Tourism isn’t the only thing that makes Hawai’i thrive,” Holt said. “I fully believe that if Hawaiians thrive, Hawai’i thrives. If Hawaiians suffer, Hawai’i suffers. So, if Hawaiians can thrive in whatever way they can do that, it’s best for all of us.”